- Home

- Harington, Donald

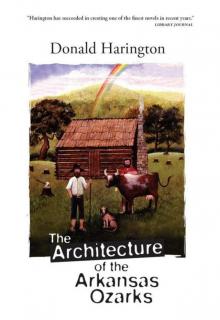

The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks

The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks Read online

The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks

By the Author

The Cherry Pit (1965)

Lightning Bug (1970)

Some Other Place. The Right Place. (1972)

The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks (1975)

Let Us Build Us a City (1986)

The Cockroaches of Stay More (1989)

The Choiring of the Trees (1991)

Ekaterina (1993)

Butterfly Weed (1996)

When Angels Rest (1998)

Thirteen Albatrosses (or, Falling off the Mountain) (2002)

With (2004)

The Pitcher Shower (2005)

Farther Along (2008)

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright ©1975 Donald Harington

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by AmazonEncore

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN: 978-1-61218-122-6

To the memory of my father (1905–1977)

and my mother (1905–1983)

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Acknowledgments

About the Author

The true basis for any serious study of the art of Architecture still lies in those indigenous, more humble buildings everywhere that are to architecture what folklore is to literature or folk song to music and with which academic architects were seldom concerned.

…These many folk structures are of the soil, natural. Though often slight, their virtue is intimately related to the environment and to the heartlife of the people. Functions are usually truthfully conceived and rendered invariably with natural feeling. Results are often beautiful and always instructive.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

from The Sovereignty of the Individual

Chapter one

We begin with an ending: the last arciform architecture in the Arkansas Ozarks. Years afterward, waking up one morning in his bedroom at the governor’s mansion in Little Rock, Jacob Ingledew was to remember the home—house, hive, hovel, we should not call it merely “hut”—of Fanshaw. There was, clearly, not a straight line in it, not a corner, not an edge, and Jacob Ingledew was to wake up one morning and stare at the four-cornered ceiling of his bedroom in the governor’s mansion, and think: box! Immediately he would jerk his elbow into his wife Sarah’s ribs, waking her, and declare, “That’s the trouble, Sarey! We’ve done went and boxed ourself in!”

“What?” she was to answer, rousing from good sleep. “You thinkin about them delegates from Washin’ton, hon?” No, he would not have been thinking about the delegates to Washington, but at her mention of them, he was to give over to sleep again in an effort not to think about them, and he was to forget Fanshaw’s home and forget feeling boxed, and go on forever dwelling in boxes of various shapes and sizes.

The home of Fanshaw—our illustration is purely conjectural, based largely on word-of-mouth description; like structures in some of the other illustrations in this study, it no longer exists; Jacob Ingledew moved it, after Fanshaw left, to his backyard, where he used it as a corncrib for several years until it logically fell victim to rot and termites, and disintegrated—looks deceptively small; actually both pens (it was bigeminal, or, to employ the term that we will have frequent recourse to, was an architectural “duple”) were nearly ten feet high and almost thirteen feet in diameter; Fanshaw, who was uncommonly tall for his race, over six feet, was required to stoop only slightly in order to exit his door, while his wife did not have to stoop at all.

Fanshaw was stooping to exit his door when Jacob Ingledew first laid eyes on him. Jacob Ingledew with his brother Noah had come with two saddlebagged mules some six hundred miles from Warren County, Tennessee, their birthplace and rearing-place; on a hazardous journey into an unknown wilderness the two brothers had palliated their nervousness by virtually chain-smoking their pipes, with the result that their supply of tobacco had been exhausted for nearly a week before they stumbled upon the village—or camp—of Fanshaw. It was situated in a clearing on the banks of Swains Creek approximately where Doc Plowright’s spread would later be, in a narrow winding valley that snaked along through five mountains, each a thousand feet higher than the valley. At the first sight of it, Noah Ingledew retreated, refusing to go nearer. From the woods on the hillside, Jacob Ingledew watched the camp for three and one-half hours before Fanshaw emerged, stooping, from his house. Jacob decided that the village, which consisted of twelve other dwellings similar to the one in our illustration, must be deserted except for Fanshaw. A field to one side of the village was devoted to the cultivation of corn, squash, beans, and, Jacob had been pleased to see, tobacco. Although Jacob, like all Ingledew men, was uncommonly shy, so great was his desire for tobacco that, after bobbing his prominent Adam’s apple a couple of times, he began walking toward Fanshaw. Instantly Fanshaw saw him and kept his eyes fastened upon him the whole length of his approach. Jacob Ingledew walked slowly to signify he was friendly.

Fanshaw descried a man of his own height, tall, dressed in buckskin jacket and trousers, wearing a headpiece made from the skin and tail of a raccoon, thin, blue-eyed, brown-haired, long-nosed, and carrying not a rifle but a half-gallon jug with corncob stopper.

Jacob Ingledew saw a man of his own height, tall, dressed in buckskin moccasins and leggings that covered only the legs, the space between breeched with a breech clout, wearing a headpiece (actually just a bandeau) of beaver skin, eagle fathers in the roach of his hair, muscular, dark-eyed, bronze-skinned, long-nosed and naked from the waist up except for a necklace of several dozen bear claws.

Jacob Ingledew spoke, rather noisily from nervousness: “How! You habbum ’baccy? Me swappum firewater for ’baccy. Sabbe?”

“Quite,” said Fanshaw. Jacob Ingledew misinterpreted this as “Quiet,” and began looking around, wondering if the others were sleeping, although it was well into the afternoon. Actually, Fanshaw had spoken in the manner of his namesake, George W. Featherstonehaugh, a British geologist who had explored the Ozarks a few years previously and had been welcomed by Wah Ti An Kah, as he was known before his fellow tribesmen jokingly nicknamed him after their guest because he spent so much time in dialogue with the visitor, even to the point of taking pains to master the visitor’s language.

Fanshaw’s dwelling, like the others, was made of long slender poles cut, appropriately enough, from the bois d’arc tree, or Osageorange (I will discuss in due course the significance of the name bois d’arc, still today called “bodark,” which fits so perfectly with all the other thumping arks of our study). Both ends of these poles were sharpened and then the poles were bent like a bow and the ends stuck into the ground, forming a large arch which was actually a parabola—and most architectural hi

storians agree that the parabolic is the most graceful, not to say strongest, of all arch forms. As may be seen in our illustration, these arched poles were interwoven as they crossed in the smoke-hole at the top; the result was literally a paraboloid, an inverted basketry paraboloid. Marvelous! Over this framework reeds, cattails and other thatch materials were interwoven; as a shelter it was weatherproof; a negligible amount of water poured through the smoke-hole during a heavy rainstorm but was absorbed by woven mats covering the earthen floor which were hung out to dry in the beautiful sunshine that often comes to the Ozarks.

Portable? Yes, “quite portable,” Fanshaw explained later that afternoon when both men were warmed by firewater, Tennessee sour mash nearly comparable, or possibly even superior in some respects, to the Jack Daniels of our time…and Fanshaw’s cured tobacco wasn’t such a bad product itself. Jacob Ingledew was on his third pipeful. (Noah Ingledew still wouldn’t come out of the woods. Noah Ingledew never would work up the nerve to come and talk to Fanshaw, even though Jacob later told him, “Why, that injun kin talk ary bit as good as you or me. Better, mebbe.”)

“A gentleman and his squaw,” Fanshaw explained over the firewater, “can lift and transport their domicile over great distances where the woods are not, or, where the woods are, disassemble and reassemble. If Wahkontah—he whom you address ‘God’—wanted gentlemen to stay in one place he would make the world stand still; but he in his infinite wisdom made it always to change, so birds and animals can move and always have green grass and ripe berries, sunlight to work and play, and night to sleep, always changing, everything for good, the earth and bodies of the skies, forever and ever…” At that point a pretty Indian woman appeared briefly in the door of Fanshaw’s house and spoke gently to Fanshaw in a language that Jacob Ingledew had never heard, then withdrew, presumably into the second of the two units in the duple. Fanshaw chuckled and said to Jacob Ingledew: “The lady thinks I talk too much.” He stood up and gave Jacob his hand, saying, “Do come again, brother.”

But it was a long time before Jacob Ingledew visited again and that was after Fanshaw had come to him. “Jist too blamed tard to ’sociate,” Jacob explained, pointing at the work that he and his brother were doing, the construction of their cabin (see our illustration to the following chapter). There had been some argument between the brothers over settling here. Noah Ingledew did not want to build in the vicinity of Indians. Jacob Ingledew liked the landscape, and besides, these Indians were friendly, and besides that, there were only two of them, Fanshaw having told him that the other members of the tribe had gone off on a hunting trip over a year previously and had not returned. As a result of having imbibed Featherstonehaugh’s firewater too freely, Fanshaw had broken his leg in a fall from his horse at the outset of the hunting trip, and was required to remain behind. He was skeptical that the others would return. He hoped they would, of course, but it had been such a long time since they had gone hunting, and he had had plenty of spare time to imagine the worst: they had met their enemies the Cherokees and been defeated, or met the blue-coat government men who forced them westward into reservations. He did not know. He still walked with a limp.

Jacob and Noah Ingledew worked from sunup to sundown for a fortnight building their cabin. For a discussion of their methods, we must await the next chapter, but suffice it to say here that this work was drudgery, although it lasted only a fortnight. At the end of that time, Fanshaw sought Jacob out (Noah scampered off into the woods as the aborigine approached and wouldn’t come back until he had left, a couple of hours later). Jacob Ingledew passed his jug to Fanshaw, realizing that now his cabin was nearly finished he could get his corn planted but even so it was going to be a dry summer, “dry” before he could get a new run of whiskey made. He told Fanshaw that he was just too tired at the end of each day building his cabin to visit him again.

Fanshaw studied the Ingledew cabin, scratching his chin. He just looked at it for a long time, walking all the way around it like a bird studying some other bird’s strange nest. Not portable, he observed. But worse, to his point of view, it was all square, foursquare, quadriform, there was not a curved edge to it, not one. After passing the jug back and forth between them for a while, they got into a long argument about architecture. I will repeat here only the end of the argument, the point at which it stopped. Although we may be sure that Fanshaw did not have the word “organic” in his vocabulary, let alone understand what is meant by organic architecture, he had a sense of a dwelling’s belonging to the landscape and fitting in with it, and he was trying to boast of how his own dwelling expressed this feeling in a way that the Ingledew cabin did not. He looked out across the rolling hills and pointed toward the gently rounded double-top of what later would be locally called Big Tits Mountain. “My house,” he boasted, “is of the same shape.”

“Yeah?” said Jacob Ingledew, and pointed toward the peak of what later would be called Ingledew Mountain. “Wal, how about that un?” The top of Ingledew Mountain forms a triangular peak of almost the same geometric angles as the gable roof of the Ingledew cabin. Fanshaw just looked at him and grinned.

Fanshaw changed the subject by inquiring whether or not Jacob’s “lady” was “at home.” Jacob Ingledew blushed and hemmed and hawed and said he aint never had ary, for the fact was that an Ingledew man brave enough to approach a savage Indian would never, could never have approached a female, at least not one above the age of, say, eleven. Jacob Ingledew changed the subject by saying that there wasn’t nobody here but him and his brother, and his brother wasn’t here right now because he was scared shitless of Indians, although in most other respects his brother was brave and fearless and had recently killed a panther by ramming his fist down its throat, although he had a few ugly scars on his arm to show for it.

After a couple of hours of drink and talk, Fanshaw got up to go. “Stay more,” Jacob invited him. “Hell, you jist got here.” But Fanshaw politely explained that his lady would be unhappy if he tarried further, and he must return to her. The pattern of this parting would be duplicated on a number of subsequent occasions, always with Jacob inviting him to “stay more”—this was not necessarily because Jacob Ingledew craved his company, although he did in fact very much enjoy Fanshaw’s visits, but a matter of formality, a custom let us say, of his people. One always urges a departing guest to remain. Yet Fanshaw could not help but remark upon this custom to his wife because among his own people the exact reverse is the case: when a guest has stayed as long as he wants to, his host senses it and sends him packing with an Indian expression which, if translated into modern idiom, would most literally be “Haul ass” or perhaps even “Fuck off.” Fanshaw’s wife was amused by the term “stay more” in the Indian equivalent into which he translated it for her. In time, it got to where whenever Fanshaw was leaving his house to go visit Jacob Ingledew, he would tell his wife that he was going to Stay More. Some folks even today think that it was Jacob and/or Noah Ingledew who gave the town its name, when in fact it was an aborigine, and the significance of the name, in its rustic ambivalence, is going to have, we will find, many ramifications, some of them poignant. We must not allow ourselves to feel that this is entirely a happy story.

But it is of Fanshaw’s house that I should speak. Why was it bigeminal, that is, a duple? Not visible in our illustration is the other door, on the other side—the west door to the other unit. There may or may not have been an interior connecting door as well; unfortunately, information on this point has been impossible to obtain. One would logically think that there was an interior connecting door, one would want to believe so, at any rate, but Jacob Ingledew, who was, on at least several occasions, inside the dwelling, simply neglected ever to mention whether or not there was an interior connecting door. The first time he asked Fanshaw why his house was bigeminal (which wasn’t the word he used; he said “divided” although that is not accurate, for, as one can see, the two units of the building are not divided at all, but very strongly conjoined), Fanshaw si

mply replied that it was “traditional.” Later on, when Jacob Ingledew raised the matter again, Fanshaw could only explain: “That is hers, this is mine.” Naturally Jacob Ingledew would have been too embarrassed to ask Fanshaw whether this meant that they slept separately.

It was learned that Fanshaw himself had not built his house. He had helped to build a number of others, but he had not built this one. He explained. Among his people, the most desirable and eligible young gentlemen are actively sought out by the maidens for the purpose of—he could not remember the English word for it, but it is the state of being man and squaw. The maiden expresses her wish for the young gentleman of her choice by giving him a piece of bread made of maize. Of course the young gentleman has the right to reject her proposal by returning the maize-bread to her. But if he wants her, he keeps the bread. Together they plan a public festival at which they will announce their wish to enter the state of man and squaw. The whole village, then, as a token of joy, build the dwellingplace for the couple in one afternoon. That is the entire ceremony.

“It is simple,” Fanshaw observed. “No words need be spoken, other than many exclamations of joy by the people as they build the domicile. A lodge-raising is a most noisy festival, but it is not in words. Much meat is eaten. The blessed couple afterward are too full of meat to do the—I did not ever learn what you call it in English—the, when in darkness, one-on-top-together-fastened-between. Do you know it? No? Pity. It is with much joy.” There was a legend among his people that this frolic was responsible for the girl’s production of an infant after nine moons. But Fanshaw’s lady had never produced an infant, although, with little else to do but tend their garden patch and hunt an occasional wild turkey, they spent most of their time in one-on-top-together-fastened-between.

The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks

The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks